With words and images on life's side

An illustrated devotional ten years in the making

By Eyvind Skeie

On the way to the source

Vann av Klippen (~ Water from the Rock) is a heavily illustrated devotional book with Scripture meditations following the year of the Church. In the home, such a book can be used for personal reading and be read aloud from, for example, in connection with breakfast or other meals. The book also has a powerful aesthetic dimension through its design and its use of text and images on the pages. It thus lends itself to be placed on the coffee table or some other prominent place in the home, and then people living there can follow the meditations from week to week or let the illustrations speak for themselves.

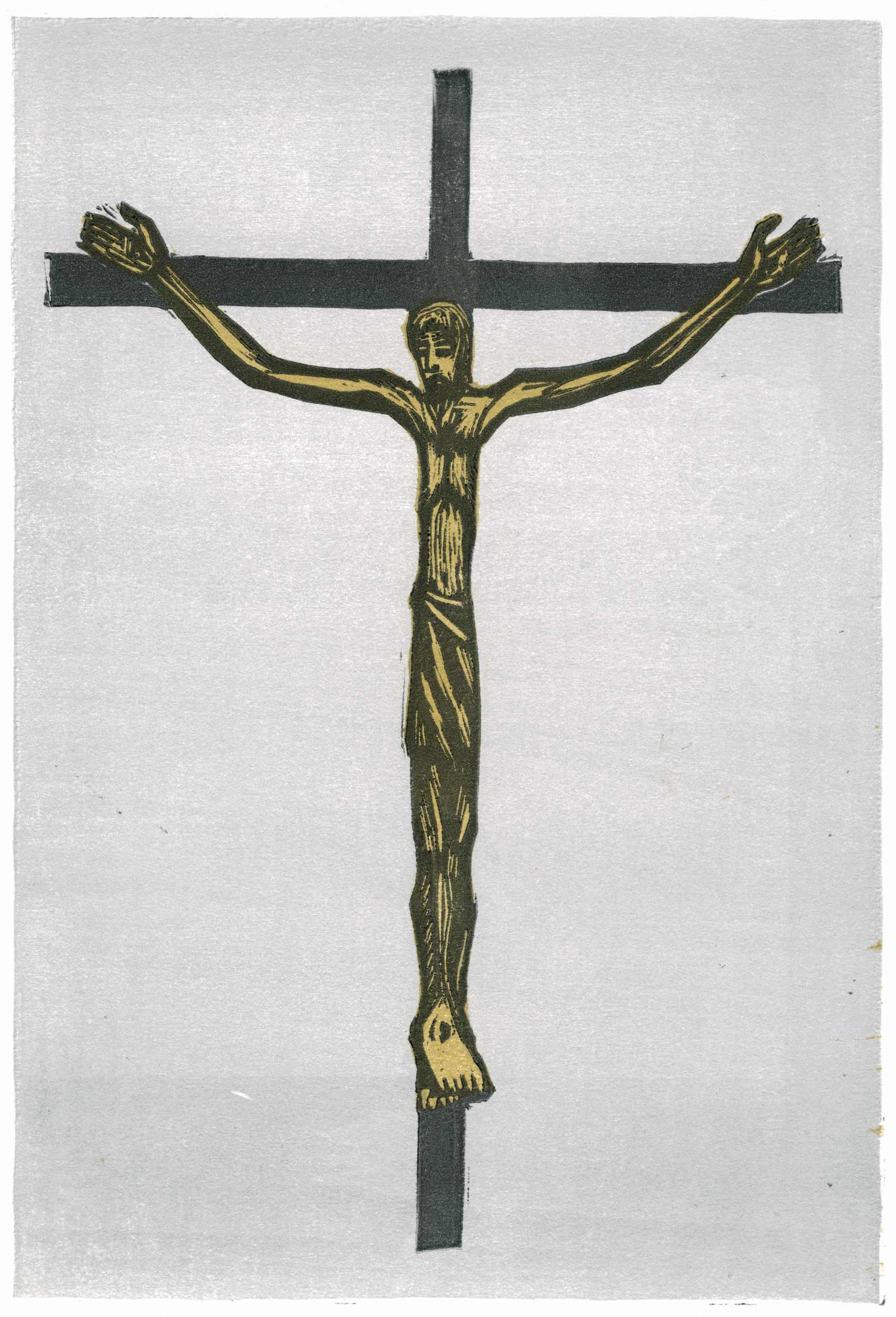

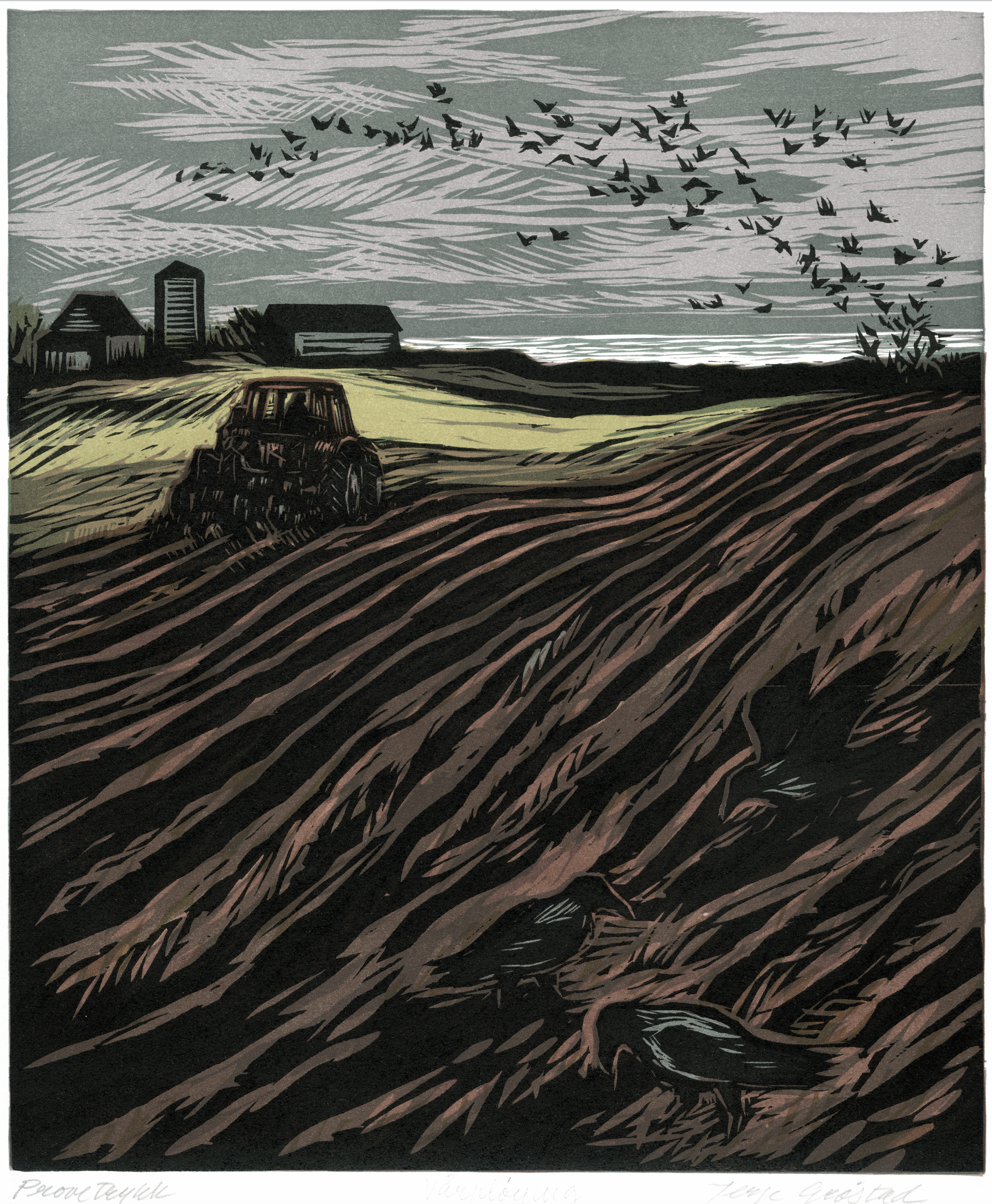

Twenty-five years ago, when the artist Terje Grøstad and I embarked on the long-term journey of producing the artwork and the meditations for this book, it was out of a personal desire to achieve something that we ourselves would be able to use on our walk through the days of the year. We wanted to create something that could give our own lives a framework of reflection and prayer, but without losing touch with our own questions, our wordlessness. Therefore, we wanted the message in text and artwork to be both open and close to the human experience.

It took about ten years for Terje Grøstad and I to make Vann av Klippen. This does not mean that we worked with the texts and artworks every single day during all these years. But this big collaborative project was always on our minds. We met regularly at Terje’s home in Flatdal, Norway, and the book slowly emerged.

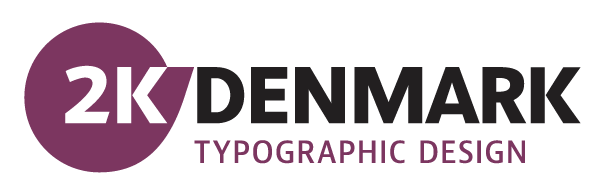

It was Terje who had the most significant work physically. For each of the book’s almost three hundred pictures, he first made sketches. These sketches were discussed between us. Then Terje started to create the final image on the wooden boards he was going to use.

Depending on the colour use and complexity of the picture, Terje had to cut out different plates. Here is where Terje showed his impressive craftmanship. He had a unique ability to mix the inks on the palette and then bring out the right colour shade in every single part of the image, whether it was one, two or three layers of colour in this specific place.

He was a master at bringing out exactly the colour mood he saw before his inner eye, whether it was the gloomy hue of autumn or the sharp contrasts of the morning of Creation. If the result was not as he had imagined, he did all the work again. He created, evaluated, rejected and retained, without ever choosing the simplest solution. It taught me a lot about professional diligence and faithfulness.

For my part, I worked with the texts. I read many of them to Terje and received an immediate response. He did not always say much, but it was still clear what he meant. Afterwards, I often had to continue working with the expressions of the message we sought to communicate.

We wanted to create something that could give an impression of the seasons of life and faith, something that was durable and something close to Jesus. We wanted to put some of our own faith and our testimony into it, but at the same time leave it open to the expressions of faith and attitudes of others.

Between words and wordlessness

It is said to have been Francis of Assisi who made the statement that “the gospel must be preached, if necessary with words.” It is a statement that links the Christian service to others directly with the mission of the Church, as given through the Great Commission. The words of St. Francis can be perceived as quite provocative, seen from both a pastoral and diaconal point of view.

On the pastoral side, one must ask oneself whether this can really be right. Is it not, however, the preaching of words that plays a crucial role in the Christian congregation’s missionary work? On the diaconal side, one has to wonder whether the wordless social service of the Church, the Diakonia, can be sufficient to say that one has fulfilled Jesus’ command to his followers to go out and make all people disciples.

Throughout the history of the Diakonia, several ways have been found to facilitate disciple-making. Sometimes the word has come first. Diakonia has then been seen as a secondary endeavour. Acts of mercy that did not directly emerge from the ministry were not considered Diakonia but rather a form of public, social activity.

But for others, the Diakonia unfolded best without words, whether it was in the extension of the congregation’s own activities or took place in public as in the modern welfare state. Here, the goal was not the possible preaching that could accompany the works of mercy but the works themselves. There is a tension in this, a tension that is also found in the quoted words of St. Francis, whether he has said them so or not.

A fruitful tension

Nevertheless, the tension in the quote is a fruitful one. It is hidden in the first half of the sentence, “the gospel must be preached,” but clearly emerges in the last part: “if necessary with words.”

It is possible to understand the words “the gospel must be preached” so that it does not unilaterally emphasize the preaching of the words as a vehicle for the “Christian presence.” Believers are called to be close to people in a way that is related to the Gospel—that which is about God’s grace in Jesus Christ. Those who believe should be “fellow human beings of grace.” This means that they must stand on the side of life and the side of the forces of life in the face of death and the forces of death. This applies whether these deadly forces appear as physical ailments and diseases, as mental illness and pain or as social distress, poverty and injustice.

As fellow human beings of grace, we all need a guideline for meeting others and being fully present in these meetings. The statement of Francis of Assisi puts us on track. Our presence must be lived out in the exciting space between wordlessness and words. And it must be a presence that begins with mercy, in the good deed of wordless mercifulness.

In the encounter with our fellow human being, with the Other, we must therefore take upon us the other’s distress and pain of life in such a way that we stop hiding behind words. We must dare to expose ourselves to the other person’s pain and distress in life to such an extent that we let go of all well-meant words and become silent.

Then we are at the base point from where the merciful deed arises, which can then, if necessary, be followed by our words. Our fellow human who hears these words will not listen to them from outside. They will not be cold words, but warm. The words have received their warmth through compassion, sympathy, or empathic attitude, if you will. We cannot become “fellow human beings of grace” without first establishing such a form of closeness.

Life interpretation

A space of reciprocity is created, where both we and the other are equally present. In this space, words can regain their validity and power. This is necessary because we humans need words when we have to account for our experience and interpret our own lives.

As humans, we are the only creatures who are able to sustain experiences, sensory impressions and emotions using the tools of language. The fact that we can use the words for all this separates us from the animals. Yes, in fact, we can think that our ability to use words in speech and writing is part of our characteristic of being created in the image of God.

Through the words, we can not only maintain our experiences, but we are also provided with an exceptional opportunity and the ability to interpret them from several perspectives. One of these perspectives can be about our relationship to ourselves, our own body and our mind, another about interpersonal relationships, a third about moral aspects, while a fourth can affect the spiritual dimension in our lives.

We all need references, help and inspiration for this form of life interpretation. For some, the conversation with others is such a help; others seek reflection in nature, while for others, art experiences through music, images and literature are of great importance.

Literature for the journey of life

Life interpretation is not something we humans are done with once and for all. This applies regardless of whether we have a firmly established view of life, a belief in God or not. Our need to interpret our lives is closely linked to what happens to us and our loved ones on our journey through time, through all the events of life for better or worse. We need to put our experiences and feelings into words and thus form the deeper pattern of our lives.

Throughout cultural history, there has been a separate literary genre that has dealt with this form of interpretation of life, whether it has had a philosophical, therapeutic or religious starting point. “Vann av Klippen” belongs to this literary genre. Here the reader will find words and artwork arranged by calendar year, seasons and church year. This is how the reader is invited on a walk through various outer and inner landscapes.

Behind the texts in the book lies a deep respect for both the vulnerability and greatness of the individual human being, but also the Christian image of God, not least as it is depicted in Jesus Christ.

Reaching the finishing line

The book Vann av Klippen was launched in Kirkens Hus (~The House of the Church) in Oslo, Norway, on November 5, 2007. On that day, I turned 60 years old. It was a great birthday present to see the book and Terje’s artwork on display. It was also a great gift to see Terje’s joy and pride that we had finally reached the finish line.

With us on this day was also the book designer and friend Klaus E. Krogh. In the last couple of years before the publication, he had made a great effort to finish the book. He had wise and inspiring suggestions and encouragements for the two of us who worked with text and images. For me personally, it was exciting to witness the dialogue between Terje and Klaus about the artwork and its motifs. Sometimes it became intense as both Terje and Klaus had clear opinions about it all. But the final result benefited from it!

A unique fruit of the collaboration between Terje and Klaus is the typeface used throughout in Vann av Klippen. All the glyphs were first cut into wood and printed on paper by Terje. Then they were processed digitally by Klaus and his staff at 2K/DENMARK in Aarhus. The result was the 2K/GRØSTAD typeface.

Crossing the finish line

July 10, 2011, Terje Grøstad died. As the officiating priest at his funeral, I had the opportunity to say goodbye to him, along with a large crowd of fellow Flatdal residents, family and friends from far and wide.

After the burial, I stood facing the mountain massif Skorve looking out over the large congregation that sang Fager kveldsol smiler (~ Beautiful evening sun smiles). It felt right that Terje should rest there in Flatdal, under the mighty mountain that he had depicted in so many different ways throughout all seasons of the year.

I stood there thinking that I missed Terje, his calm, our conversations, his teasing smile, his deep anchoring in Christian faith and tradition. There were tears in many people’s eyes and fog in the air on this rainy day. Then the sun broke through the clouds. The light sent us a greeting, the light that tells us about Creation, hope, mystery and God.

With the hope that words and text in Vann av Klippen have lit and will light a spark in someone’s eyes!

Eyvind Skeie, born in Bergen in 1947, is a Norwegian pastor and author. He is also known as hymnodist, with over 50 original and translated hymns included in the official hymn book of the Norwegian church. Altogether, he has written about 600 hymns, in addition to children’s songs, popular songs and libretto for plays and church plays. Some of Eyvind Skeie’s lyrics have become commonly known in the Norwegian song culture in homes, churches, and schools. Skeie has an international involvement and has worked closely with the Coptic Church in Egypt. For over twenty years, Eyvind Skeie and Klaus Erik Krogh have had different forms of collaboration, especially in Norway and Denmark.